Starlet

The boxes I retrieved from Mum's attic are full of the useless artefacts of youth. I will throw away the diaries, the confidential letters, and the novels. We are encouraged in these times of minimal living to only keep things if they bring us joy.

So, why am I so reluctant to throw away the front and back license plates of my first car, a baby blue 1981 Toyota Starlet?

Dad found the car in the paper. I was so impressed. Three hundred and fifty pounds, or nearest offer. The old lady had owned the car from new but was now giving up driving, which was probably for the best as the septuagenarian seemed to age well into her nineties in the face of my father's ruthless bargaining. She stood motionless and exhausted in the doorway as he thrust used banknotes at her.

As we departed, Dad unclenched his fist of celebration, put the car into first gear, and gave her a cheery wave and toot. His early career as a door-to-door salesman had bestowed him with occasionally remarkable powers of negotiation. In the divorce settlement a year or so later, he left my mother and her six children a wheelbarrow and not much else.

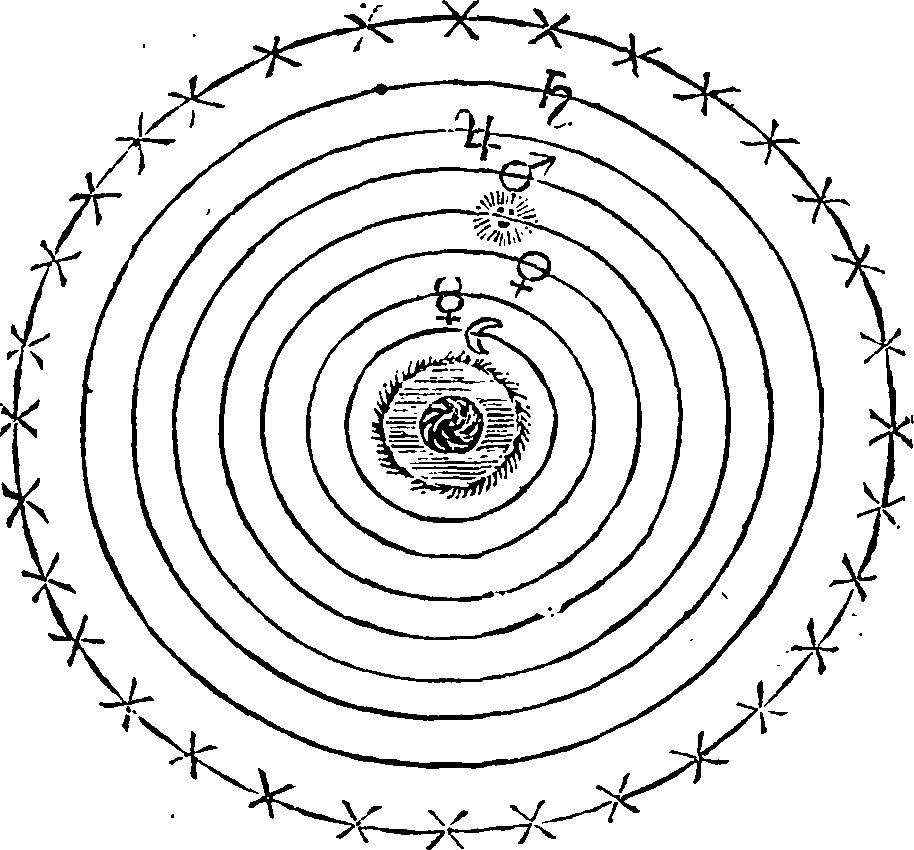

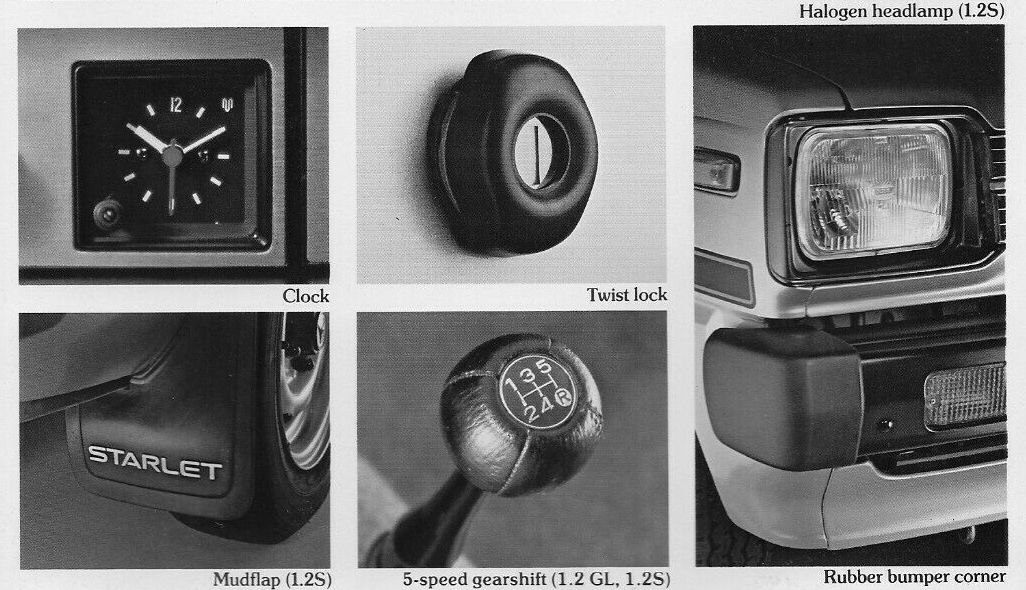

Toyota's marketing brochure, which I also found in the attic, positions the Starlet as a miraculous coupling of reliable power and executive comfort, packaged within a stylish, yet spacious, three-door hatchback.

Armchair comfort, boasts the opening page, pausing for breath before informing you that the the cabin gives plenty of space to stretch out and relax with tinted glass that makes driving easier and less tiring. It's unclear if it is the tinted glass or the mere existence of windows in the car that gives your passengers more enjoyable viewing, but it's a benefit that Toyota are keen to sell you on.

The engine is described as zippy, which is a very generous way to characterise the 16 second crawl to 62 mph (100 kph). Some minutes later, if you were lucky, you might reach the Starlet's top speed of 89 mph (143 kph). Still, extracted from a 993 cc engine and four speed gearbox, that wasn't too bad for the time.

The secret of the Starlet was its 695 kg kerbweight. I looked it up, and it weighs more than a polar bear, but less than a buffalo. The rack-and-pinion steering matched to a MacPherson strut at the front meant that animals of that size could be easily avoided if they stepped into the road unexpectedly.

The pièce de résistance was the Toyota's rear-wheel drive, coupled with 4-link location coil spring suspension and gas-filled shock absorbers. The brochure tells me that this ensures the Starlet is a positive please to drive and so easy when it comes to parking. In other words, it was excellent for making your co-drivers hoot with joy while you perform donuts late at night in an empty Halfords car park.

The brochure also advertises that it has a clock, twist lock, rubber bumpers, and four mudflaps (but only on the 1.2 GL model). It does not advertise that, in reality, the car is a hopeless heap of junk.

On a cold day, or when it rained, or when it was warm (all the days, basically), the Starlet would steam up within seconds, reducing visibility to zero. I kept a cloth in the car, with which I'd wipe a small porthole to peer through as I hurtled down single-track roads. My glasses also steamed up, meaning that I had to double porthole just to stay alive.

The car was a magnet for rust. The moss growing in the metal runners on the roof should have been the first warning sign. Dad taught me the basics of mechanical maintenance, how to check the oil and tyres and replace basic parts, how to wash a car, wheels first then top-down. I still wash my car like this.

Dad was at his best when teaching me to drive. We started on a disused part of dual carriageway, which I could kangaroo down without threatening the lives of others. Once on the open road, I had a tendency to brake late, imperilling other drivers and their vehicles. This made Dad nervous and when he was nervous his voice would start to squeak, making him sound like a hysterical Mickey Mouse as he urged me to mind the parked cars and BRAKE HARDER, FOR CHRIST'S SAKE.

Once I passed my test, I made full use of both my liberty and the Starlet's zippy performance to challenge tuned Ford Escorts to drag races. For most hatchbacks, this was a fool's errand, but I knew the Starlet was quick over the first 50 metres. It had a long first gear, meaning no gear change, meaning no drop in revs. If you could manage the wheel spin, you could surprise a more powerful car.

One time, a little too eager, I ended up looking at the wrong set of traffic lights. When the light to allow cars to turn left went green, I thought it was for me. I dumped the handbrake, the rear wheels gripped, and I flew through two sets of red lights and across a busy intersection, miraculously evading cars coming from both sides. My passenger and I pulled over and laughed nervously until we ran out of tears. This manoeuvre was not mentioned in my father's driving lessons.

The Starlet enabled me to work night shifts at Woolworths, stacking shelves, and I became junior manager on the music desk. Dad encouraged me to put money aside for essential repairs. I filled my bank account with more money than I'd ever held in my hands and then spent it all on an in-car CD player worth more than the car itself. I trembled as I handed over the money.

At 16, I agonised over leaving school. The real lesson Dad taught me was that the car was not the brochure; it was much more than that. This was a vehicle for freedom and independence. It signposted new horizons that he encouraged me to drive towards at speed, albeit a reasonable one for the prevailing traffic conditions. Sometimes you have to leave things behind, he said. Start again.

At 17, I left school and went to a sixth-form college, a thirty minute drive away, shuttled by the tiny Toyota. I made new friends. After lessons, we would race down to the beach where we sometimes stayed overnight, building firepits in the pebbles and laughing into the summer wind before taking advantage of the Starlet's fully reclining seats to get some sleep, all five of us snuggled together in sleeping bags, plenty of space to stretch out and relax. I don't know the people any more, but in those moments they felt like a family I had chosen.

Back home, things were fraught. Mum threw her wedding ring out the bedroom window. Dad said she hadn't done enough to ruin the marriage already and proceeded to smash up some photo frames in the kitchen. Packed suitcases were placed, threateningly, by the front door.

Dad left for good the night before my first exam. I flunked it and drove out to the Hurtwood, an ancient forest of oaks and beeches. I parked the car in a National Trust car park and cried for an hour straight before driving to pick my sister up from school.

Exam results came around and I did better than expected, all things considered. Friends drifted away in the summer before university. I delivered things long distance in the Starlet. I broke up with my girlfriend and felt nothing. I packed boxes and put some of them in the attic.

Months later, the Starlet transported the rest of the boxes up north to university in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, an eight-hour trip in horizontal rain, past the seven hills of Sheffield and the services at Scotch Corner. In the glove box was the Starlet's brochure and a small bag of marijuana, which I intended to use to make friends.

I needed the Starlet less at university, but I would drive out every week to the Tyneside coast, watch the surfers in the white-capped waves, and read the letters Mum had written me.

She'd lost the house and was moving again. My sister got hit by a car. My brother was bullied out of his school. Five children were growing up without a parent, while the older brother, me, lost himself in T.S. Eliot, Toni Morrison and Godspeed You! Black Emperor. Sometimes the guilt and sadness came all at once, other times not at all.

When the time came around for the Starlet's annual check-up, it failed me. The floor had rusted through on the passenger side. The mechanic lifted up the carpet in the footwell and showed me the concrete floor of the workshop underneath. I felt bereft, losing my trusty steed, but also thankful that I hadn't yet killed any of my friends. They had been wearing seatbelts that were attached to nothing but a piece of beige fabric from the eighties.

In the end, I paid the mechanic 70 pounds to scrap the Starlet and send the parts to Nigeria. He said they were very valuable in that part of the world. Why are you not paying me then? I asked, but he pretended not to hear. Just in time, I remembered to remove the CD player before it was crushed. I added the license plates to the box in the attic.

Twenty years later, holding the plates in my hands, the initial, glossy allure of the Starlet still lives and it brings me joy. In the brochure, I am the jaunty young driver winding through the English countryside, enjoying the Starlet's low noise luxury and panoramic visibility.

Experiences splutter into life, turning over as enduring moments of connection and sadness that exist as both spark and coil, distribution and displacement, a magnetic field forming, lines of flux, memories that are more than the sum of their parts.

The reality lives too. The leaking window seals, broken heaters, and the sagging parcel shelf. The faulty door lock and the window that I had to replace after it was shattered by thieves. One snowy evening, the headlights failed, and the Starlet nearly betrayed me into a ditch. Sometimes things decline both slowly and suddenly.

Keeping these license plates is not a rebellion against time. Nostalgia is valuable when it is all things: the brochure, the experience, and the reality. To only become misty-eyed or enthralled or angry, is to miss the point. The license plates are a coping mechanism, a preparation for new adventures, and a message to myself. Everything gets broken up for parts eventually.

Thanks to my Foster editors, Jordan T. Jones and Ryan Williams. And thanks to Julia for bringing me joy.

Like what you read today? Forward to someone you love. Subscribers get creative non-fiction and essays exploring different themes, every Saturday. And that makes me happy.