Leafcutter Bees

Like ninety percent of bees (and almost all writers), leafcutter bees are solitary, working alone on projects they fear they may never finish.

Leafcutter bees build nests in any cavity they can find: old trees, snail shells, concrete walls or, as they did last summer, in tunnels underneath the plants on my balcony.

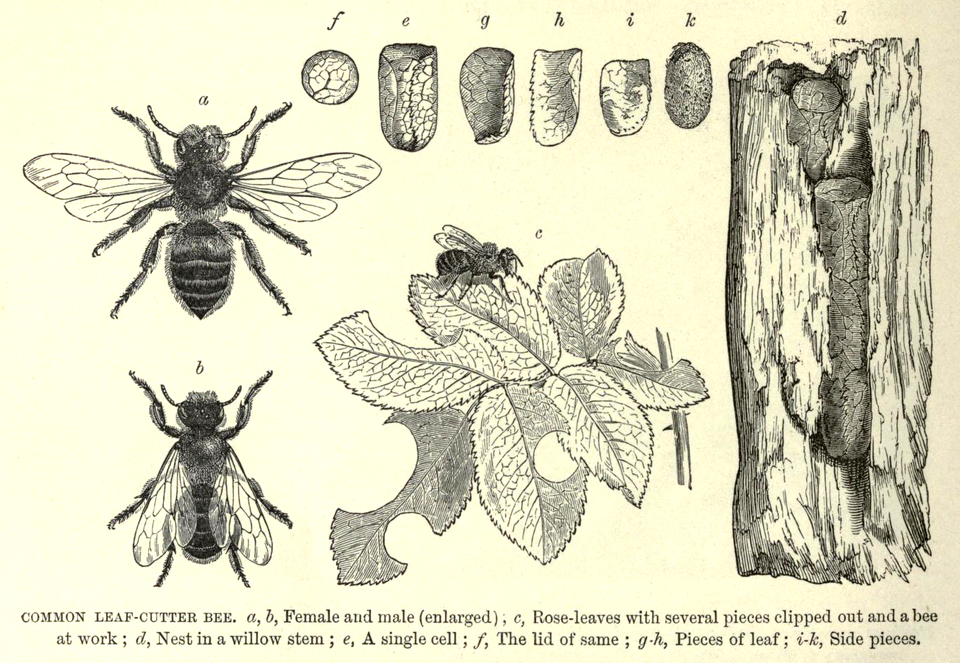

They cut sections of leaf, perfectly-sized for their task, and line their nests with it. Inside, they lay an egg, leave enough pollen for the larva to survive, and then seal up the chamber. Tunnels can contain many chambers, each of which will be the home to a young bee. The following spring, the young bees make their way out of the nest and fly away.

When a leafcutter bee undertakes its nest-building, many things can jeopardise its plan.

The cuckoo bee, its mortal enemy, might be waiting outside. Given an opportunity, the cuckoo bee invades, taking the pollen for itself, starving the larvae.

Changes in the climate are dangerous. They can alter the start of spring, causing flowers to bloom at different times. Even slight deviations in nature's timetable can mean the young bees emerge at the wrong time and miss their chance to gather food. Or, heavy rain can flood the tunnels. There is no way back from this.

My attempts at writing last summer felt similarly threatened. For the first time since records began, the Netherlands had experienced temperatures above 35°C for five days in a row. Outside, magpies argued in the gutters. Irritable herons protested the presence of impudent jackdaws. Whistling swifts hunted as the church bells chimed and moved the heavy air. The weather made me listless.

Unable to travel due to government restrictions, I looked for a distraction from challenging work circumstances, brought on by the pandemic. I hoped for an escape, of sorts. I decided to start writing again.

I shut the windows and pulled down the blinds. The glare of Coronavirus datasets, swirling pandemic conspiracies, and urgent email notifications filled the room. The apartment grew unbearably hot. Every sentence felt ruined.

Finishing anything proved impossible as I struggled to convert my lazy obsessions into something beyond a long string of poorly concealed facts. My wife watched me pace up and down. Weeks of research and drafts sat isolated in dead documents. The days were bloated with non-sequiturs and sacrificial paragraphs.

The worst part of writing is when you feel you may never complete the thing you started. When every sentence you append adds so much weight that the entire thing collapses in on itself, leaving nothing but wasted, empty hours.

So I turned to the bees for solace.

Outside on the balcony, they continued their work, building their nests. They moved, unwavering between the bushes and the plant pots, returning with expertly-cut ovals of bright green foliage. Despite the potential for failure, they persisted. What are you trying to teach me?, I asked myself.

"Who are you talking to out there?" asked my wife.

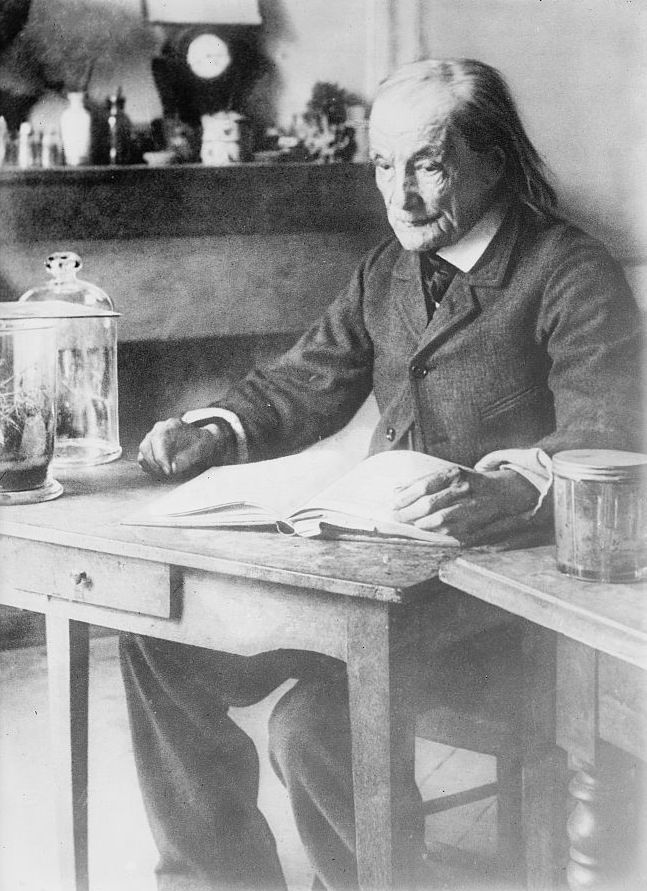

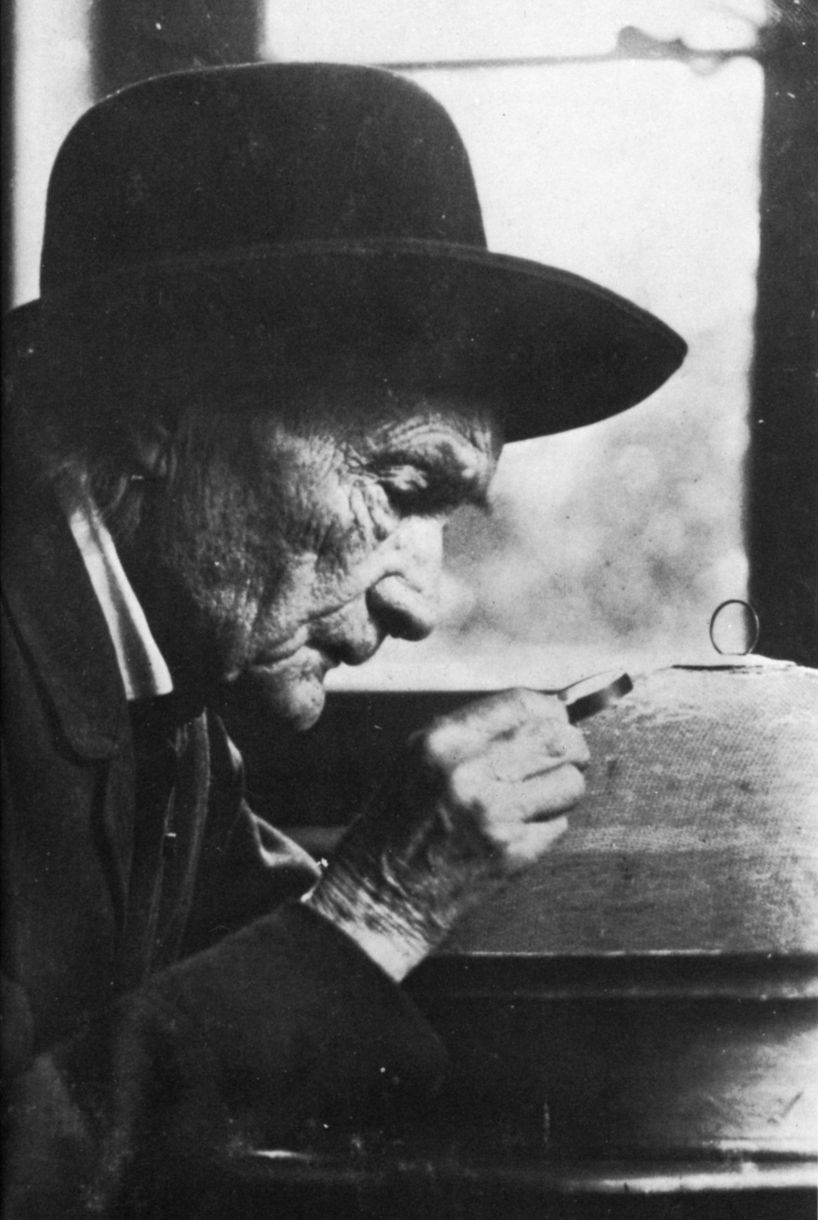

I began to research the bees and discovered the work of Jean-Henri Casimir Fabre. Fabre is the father of modern entomology, the study of insects. I always confuse this term with etymology, the study of the origin of words.

Fabre mastered both, despite being born to illiterate, poor parents in 1823 in Aveyron, France. He spent his childhood wanting two things: to observe insects, and to learn. An autodidact, he found himself unhappily making a living at the age of fourteen selling lemons at the fair of Beaucaire.

From these humble beginnings, Fabre put himself through teacher school. He became a botanist and eventually wrote Souvenirs Entomologiques, a breathtaking work of 4,000 pages published in ten series between 1879 and 1907.

Fabre was an extraordinary observer of the natural world. In Souvenirs Entomologiques, he describes the hidden lives of insects, combining rigorous field research with philosophical reflections and childhood memories. Darwin called him "an inimitable observer." Victor Hugo anointed him "the insects' Homer."

Fabre's writing is remarkable for how different it is from other scientific journals of the age. At the time, the academic world reproached him for his style, which did not obey the solemn, dry tone expected of learning material.

Instead, Fabre animated creatures on the page. Worms perform chores, beetles take care of their families, spiders possess hopes and desires. Leafcutter bees become a living pair of scissors.

"The man who knows how to use his eyes in his garden will observe, some day or other, a number of curious holes in the leaves of his lilac- and rose-trees. The author of the mischief is a grey-clad Bee, a Megachile. What mental pattern guides her scissors? What system of measurement tells her the dimensions?"

At some point, I imagine Fabre thought he would never finish Souvenirs Entomologiques. But he enlisted the help of his six children, giving them roles as researchers, leaning on their youthful curiosity. With them, he divined complex, brave lives into tiny natural worlds, writing with fascination, zeal, and affection. He drew energy from those around him, and brought it to life on the page.

One of the hallmarks of his work is that he is comfortable with the unfinished. He is happy to withhold conclusion, pursuing enquiry to a certain point before making peace with the imperfect.

"The insect excels us in practical geometry. I look upon the Leaf-cutter's pot and lid as an addition to the many other marvels of instinct that cannot be explained by mechanics; I submit it to the consideration of science; and I pass on."

Fabre's works themselves are also a marvel of instincts; they too cannot be explained by mechanics. In converting obsession into passion, he moves beyond structured, factual prose into something organic and spirited.

Slowly, the same happens with my own work. While the reader can readily observe the flaws, writing is easier now than it was last summer.

The first reason is that I have ended my isolation. A community of editors and newsletter subscribers improves my work. As with Fabre, energy from others brings life onto my page. Writing for an audience has assisted me; my writing is no longer rendered in isolated frustration. The newsletter's regularity enforces (some) continuity and consistency.

There is a second reason that writing is easier now. I have given up on the fear-inducing notion of perfection. Sometimes, done is better than perfect.

When I hit an impasse, when the writing feels like it will never be finished, I often find myself on the balcony, observing the bees. Despite the changing weather patterns and moving seasons, they have come back. Last year, their nests were flooded in a summer rainstorm. Yet, this year, they continue to ferry their precisely-trimmed leaves back to my plant pots, inadequately protected though they are. In defiance of the climate's shifts, they are lining the nests for next year's spring.

In moments when my words will improve no more, I go out and watch the leafcutters moving back and forth. Their golden bodies shine in the sun as they carry leaves many times larger than themselves.

There, thinking of Jean-Henri Casimir Fabre - seller of lemons, son of illiterate parents, poet of the natural world - I observe the leafcutter bees and make peace with the imperfect, as they have done by taking refuge in my plant pots. Then I simply submit my writing to your consideration, and I pass on.

Thanks to my Foster editors, Jillian Anthony and Ryan Williams. And thanks to Julia, for letting me pace.

If you do not already, please subscribe to my newsletter here. You'll get new creative fiction and essays exploring different themes, every Saturday.

Sources

- https://en.e-fabre.com/

- http://www.efabre.net/chapter-viii-the-leafcutters

- https://archive.org/details/lifeofjeanhenrif00fabriala/page/16/mode/2up

- https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1915/10/12/105042637.pdf